Economics In the Fantasy World

Kammesh Atputhajeyam

What Is FPL?

FPL (Fantasy Premier League) is a fantasy football game which is currently played by 10,331,796 people. To understand how economic principles are applicable to this game, we must understand how the game works. The goal is to assemble a team comprising of 15 Premier League football players with the constraint of a £100m budget. The real-life weekly performances the football players determine the points received by FPL managers. The higher the total points of an FPL team, the higher the overall rank among the other 10 million managers participating. Every FPL manager is allowed to make one change to their team each week, but for every transfer above the permitted on, they lose 4 points.

Budget Allocation

A key concept in economics is the basic economic problem. In an FPL context, this involves working out how best to allocate the £100 million budget on 15 players (that will collaboratively achieve the highest points total). In other words, managers are seeking an absolute advantage. Managers can seek to obtain two broad types of teams: balanced teams and a premium team.

Balanced teams seek to distribute the budget evenly among various positions (goalkeepers, defenders, midfielders, and forwards). Primarily, the most significant advantage is that the risk factor of banking on specific players is heavily reduced. By having players who perform consistently whilst also not being overpriced, this means that these balanced teams can achieve a comfortable number of points.

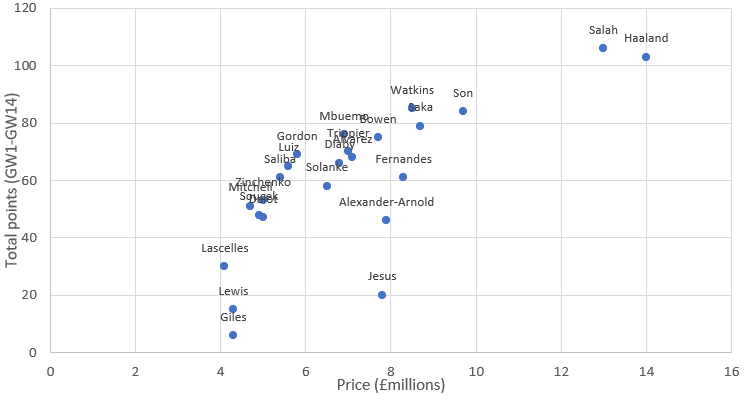

On the other hand, premium teams aim to concentrate most of the budget on expensive players. As these expensive players consistently perform well, they will pick up a high number of points. This causes an increase in the confidence that an FPL manager has towards these players. Consequently, demand for these players would increase as the aim of managers is to transfer in players who can maximise the team’s total points. Ceteris paribus (all other things being equal), as demand increases for players, the price level will also rise. Therefore, it is safe to assume that the more expensive a player, the more likely they are to score high. It is important to understand that statistically, this relationship is primarily positively correlated – there is a causal link between the performance and price of a player. This can be seen in the graph above where 25 players were randomly sampled and then plotted with price against total points (a measure of performance).

Whether a balanced or premium strategy is chosen could depend on injuries, form of the team, and morale of the player. However, this strategy is significantly riskier than the balanced team approach and, as a result, most weeks may result in a below average game week point total.

A secondary objective of managers is to maintain a high team value. At the start of the season, all teams are valued at £100m, but as players’ prices change due to performance, overall team value could increase or decrease. This also means that managers are able to make a profit by selling players who have risen in price from their initial value and use such profit to finance investment into other players.

Opportunity Cost

When making an economic choice, opportunity cost is defined as the next best alternative given up. In the case of FPL, the economic choice is transferring in a player. Bringing in a premium player may only be possible by sacrificing 2 cheaper players. Furthermore, although the objective of transferring in the player has been achieved, the manager may have to bear the cost of a 4-point deduction from taking an extra transfer. Some may argue that this point deduction system could be likened to protectionist policies, specifically a tariff. By “taxing” the trades of players after the initial free trade, this disincentivises managers for making excessive transfers. In FPL, a manager can only own 3 players form the same football team. This is like a quota, and it minimises a reliance on highly performing teams.

Improvements

One improvement to FPL, to make it more realistic to the real world, could be to ensure prices are more volatile. By fluctuating prices to a greater extent, price changes will be more responsive to real-time performances and market trends. In the real world, a characteristic of financial markets is that prices changes by the minute, as seen with exchange rates and stock prices. This could be applied in the FPL transfer market, with, instead of daily price changes, hourly ones. This would enhance the gaming experience as it would require FPL managers to remain up to date with real-time games, engaging them further with both the game and the Premier League.

A more controversial change could be to introduce budget caps for each position. Most FPL players concentrate their budget in the midfield section of their team. By changing budget caps, FPL managers would be prevented from overloading their teams with star players. Creating new caps could cause the dynamics of the game to shift, resulting in new strategies that could interrupt the status quo of FPL. For example, one potential scenario may be a £10 million cap on goalkeepers, a £35 million cap on defenders, a £30 million cap on midfielders and a £25 million cap on strikers. This would lead to the game having to become primarily focused on accurate investment in defenders.

In Practice

Of course, FPL models a very specific economic situation. And in football, injuries are common. If a player receives an injury, they are normally unable to play at least some of the upcoming matches. This is an example of an external shock. Since injured players are no longer useful economic assets, they generate negligible utility, and so the demand for them drastically falls.

Conclusion

Overall, the theories that underpin the social science of economics can also be applied to FPL, with economic agents having to consider a wide range of variables, like those mentioned previously, in order to reach their objective of maximising their utility.

Comments ()