How can the UK government and international partners reduce global extreme poverty?

Jacob Corne

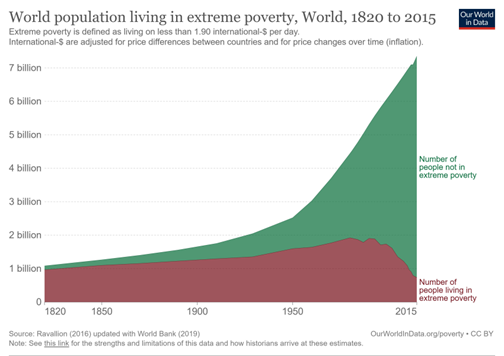

Before the policies that the UK government and international partners could introduce to reduce global extreme poverty are discussed, it is important to recognise a key distinction. Whilst poverty affects nearly half of the world’s population (United Nations, no date), extreme poverty narrows the scope to around 800 million living at an income level of below $1.90 a day (World Bank, 2019). Although the graph below suggests we are on the right trajectory, 800 million is still a huge number of people that are struggling for necessities. In fact, it is a figure that warrants a dual-strategy approach to tackling the problem, relying on foreign aid in the short term, before promoting education in poverty-stricken nations.

Figure 1 (Ravallion, 2016)

A collective system of foreign aid is initially vital to lowering extreme poverty. Through collective funding, a substantial $204 billion dollars of foreign aid was distributed in 2022, reaching an all-time high (OECD, 2022). The provision of essential supplies that came about from these funds, such as food and clean water, cannot be ignored. Mitigating malnutrition and diseases such as cholera reduces illness in areas of the world where access to healthcare is limited. Plainly, foreign aid saves lives, but it only provides a temporary solution.

Amid the many criticisms of aid is the micro-macro paradox. The problem with aid is that, despite its vital short-term impact, it destroys growth in the long term. Suppose there is a local bucket maker in a rural village, but thousands of buckets are imported as a form of foreign aid to give impoverished recipients a way to collect water. The local bucket producer goes out of business when his customers learn of free produce available. Macroeconomically, poverty had been reduced and the inequality gap narrowed. However, the local bucket producer and their workers are now unemployed – they can no longer provide for their family, and the total output for the country has marginally decreased. When these micro changes are amassed, the macro outcome therefore also involves a fall in the country’s GDP; whilst the aid has helped some people, the country as a whole has economically suffered from the foreign intervention (Moyo, 2010). Moreover, when free cash from foreign aid is available, corrupt governments rise to power and create badly run economies that are disadvantageous to invest in. This deprives the country of growth and increases unemployment and poverty. The response to this poverty is more foreign aid, revealing a brutal poverty-aid cycle (Moyo, 2010). Consequently, foreign aid should only be used until we start to see the success of a longer-term method to reduce global extreme poverty.

That longer-term method should be a worldwide education investment scheme, specifically through governments worldwide paying private corporations to build enough equipped schools to increase access to and years of high quality education.

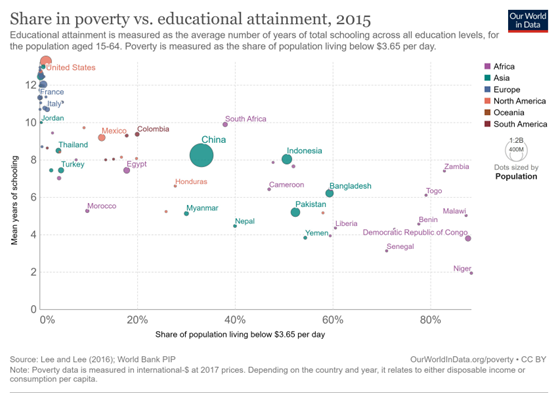

Figure 2 (Lee and Lee, 2016)

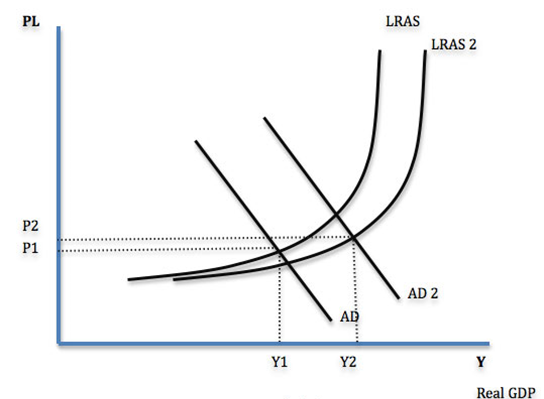

If implemented appropriately, boosting access to education and years of schooling would have the joint benefits of increased aggregate demand (AD) and long-run aggregate supply (LRAS). If more people receive a longer education, then a greater number are taught important workforce and leadership skills. This leads to a greater quality of labour, one of the factors of production. A higher quality workforce increases productivity, which is defined as the output per unit of factor of production in a given time period. When productivity rises, more can be produced in a given time period, so business costs decrease, and a subsequently higher profit margin incentivises firms to increase their supply of goods. Bolstering LRAS, this causes a greater productive potential to be reached, which demonstrates that when all resources are fully employed, more can be produced, and so there is a greater ceiling for the countries’ national income (NI).

As well as the supply-side element, educated populations are more likely to be able to find a job, as they have a greater skillset that is valued by companies. Therefore, unemployment is reduced, achieving another key macroeconomic objective. The increased employment rates mean more people receive a salary, so real incomes increase. As a result, disposable incomes are likely to increase, so more people are willing and able to buy products, meaning that consumption increases, and so AD also rises. This leads to a shift in NI from y to y1, as seen in the below diagram, and so NI increases. An increase in NI means that more goods and services can be bought, and so the quality of life will be improved, bringing people out of extreme poverty.

Figure 3 (Pettinger, 2019)

As private companies are paid to build the school instead of the government, efficiency is likely to be maximised as there is a profit-seeking motive for workers. However, it is important that national governments correctly incentivise education-supplying firms. For instance, if governments reward firms based on how many pupils attend the school, the companies may neglect the quality of education in order to produce a school with a large capacity. Instead, the public sector could pay the private sector according to the average income of the schools’ alumni. Whilst this provides issues of its own, with success not being defined solely by one’s own income, it would provide a target that is more conducive to a fulfilling education.

Furthermore, investing in education may not be politically stimulating. Traditional economics explains that governments, as self-interested economic agents, are really only charitable to attain utility from their population recognising the good deeds. Underneath their superficial altruism is pure individual egoism (Fehr and Renninger, 2004). Social media could be positively used to spread messages about new schools, whilst messages from students could be broadcast via television adverts across the globe. Although the current economic climate involves high food and energy prices, if funding was collective, then individual countries would only slightly worsen their budget deficits.

Overall, maintaining foreign aid is presently important, but a transition of investment to education is how the UK government and international partners could truly reduce global extreme poverty.

References:

Fehr, E. Renninger, S-V. (2004) The Samaritan Paradox. Scientific American Mind Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/24997549

Lee & Lee. (2016) Share in poverty vs. educational attainment Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/poverty-vs-mean-schooling

Moyo, D. (2010) Dead aid: Why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. London: Penguin Books.

Official Development Assistance (ODA) - OECD. (2022) Available at: https://www.oecd.org/dac/financing-sustainable-development/development-finance-standards/official-development-assistance.htm

Pettinger, T. (2019) Investment and economic growth, Economics Help. Available at: https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/495/economics/investment-and-economic-growth/

Ravallion, M. (2016) World population living in extreme poverty Our World in Data. Available at: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/world-population-in-extreme-poverty-absolute

United Nations, Addressing poverty (no date). Available at: https://www.un.org/en/academic-impact/addressing-poverty

Comments ()