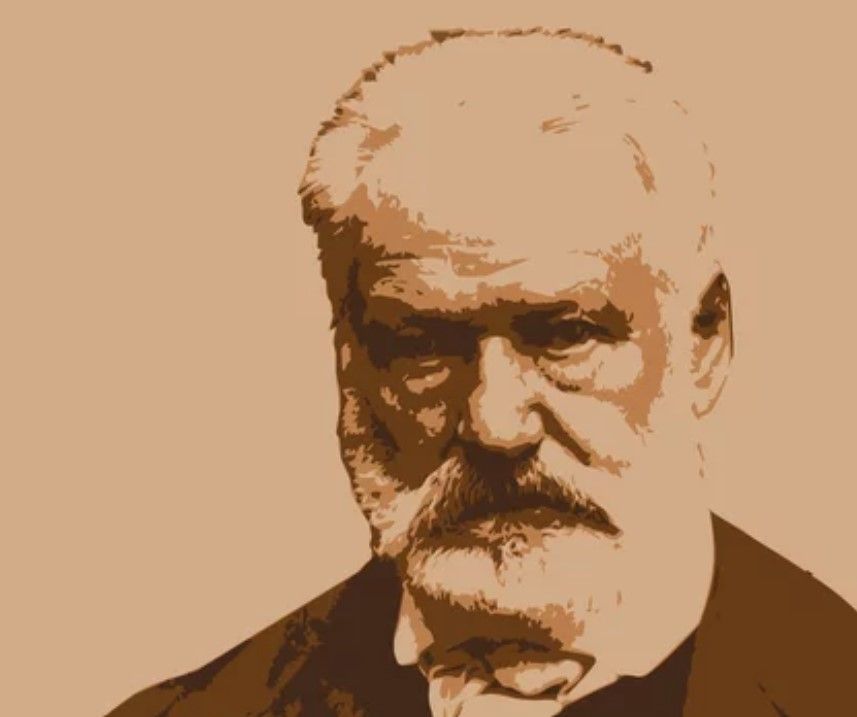

Les Misérables - Victor Hugo’s revolutions and digressions

Stanley Hardy

About one thousand pages into Les Misérables, Victor Hugo disrupts the main narrative to ask a question: ‘What constitutes an emeute, a riot?’ He then proceeds to answer that question: ‘Nothing and everything. An electricity gradually released, a flame suddenly leaping forth, a drifting force, a passing wind. This wind brushes heads that think, dreaming minds and suffering souls, burning passions, howling miseries, and sweeps them away.’

This is indeed an answer, a relevant answer to a relevant question. One that offers pathos, a dramatic realisation that mirrors the struggles of the characters and the purposes that drive them. It is a spelling out of the events of the previous chapter, one in which the old man M. Mabeuf’s disillusionment with poverty leads him to follow the sounds of revolution – eventually dying a martyr on the barricade, shouting “Vive le révolution! Vive la république! Fraternity! Equality! And death!”

It is a sentiment that Hugo understands in the answer to this question, one that runs deep within the hearts of many of the characters of the book. Yet this answer to ‘the surface of the question’ doesn’t seem to satisfy him. And thus, about twenty pages pass before we return to the narrative, having answered what is ‘the essential question’. Twenty pages of long-drawn-out discussion of history, and philosophy, and politics. As is with the nature of these Hugoic digressions, of which this is one of many, ranging from Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo to the extensive history of the Paris sewers. Twenty pages isn’t that long considering the fifty or so spent on Waterloo.

Thus begs the question of why? What’s the point of spending so much time on these tangents? Does it not just break the narrative? The answer to this latter question is simply, no. To answer the more useful question of ‘why?’, I equivocally ask a question of my own: What is the purpose of literature of this kind? It is helpful that Hugo himself gives a rather direct answer to this, in the novel’s preface:

So long as there shall exist, by reason of law and custom, a social condemnation which, in the midst of civilization, artificially creates a hell on earth, and complicates with human fatality a destiny that is divine; so long as the three problems of the century – the degradation of man by the exploitation of his labour, the ruin of woman by starvation, and the atrophy of childhood by physical and spiritual night – are not solved; so long as, in certain regions, social asphyxia shall be possible; in other words, and from a still broader point of view, so long as ignorance and misery remain on earth, there should be a need for books such as this.

Hauteville House, 1862

It is a quite direct manifesto of intent with little ambiguity, beautifully put into prose. It is a sentiment that runs deep within the entire text, notably in the struggles of the characters with poverty and injustice, with the law of God and the law of man. A great effort is made for us to completely understand these struggles, with much emphasis placed on every single thought and action that occurs. It is similar to the digressions. To completely fully realise this struggle, one must not only understand empathetically, but intellectually with the context and history that surrounds personal experience. This seeming dichotomy is emphasised by the melding of the operatic, heightened narrative with the painstaking detail put into every scene, every setting, and of course with that of the digressions embedded within. Thus, I would argue these so-called ‘digressions’ are very much relevant, context to enrich the world of Jean Valjean and Cosette, a world that is very much our own. As can be implied by the underlying philosophy of the preface, there should not be a barrier between story and reality, as one directly informs the other. Even with the lengthy discussions on convents, or briefer interludes into Gavroche’s poetry, that same principle of maintaining a depth to not only the fiction, but the world around us, is present to defeat ignorance, the apathy of those to the world and others around them. Even the seeming insignificance of argot slang, or the Paris sewers, can and do have far-reaching impacts, from the situations of the characters, or the greater machinations of society.

Take Hugo’s Waterloo, which despite taking place many years before much of the events of the novel, has lasting relevance to the political and personal climate of the narrative, with many characters being directly impacted by the fallout of that battle – notably Marius – of whom contributed to the outbreak of the June 1832 Insurrection – perhaps the most persistent image of the book, helped in no small part by the major adaptations of the story bringing it to the cultural forefront. The historical impacts the personal, which in turn forges new historical precedence. In abridging the work, the symbiosis between the historical and personal are diminished, thus undermining this vision of total understanding – something I would argue both major adaptations failed to achieve, being more so concerned with making an impressively sentimental and unnuanced story. I digress.

To return to that of the revolution, its placement is of no random chance, as is with all his digressions, though it is perhaps the most pertinent. As I have touched upon before, Hugo’s use of characters is as important in conveying themes and messages, as with the aforementioned M. Mabeuf. It is however quite impossible to talk about characters and politics and revolution without mentioning the friends of the ABC – a group of revolutionary students that serve as the living embodiment of the digression, introduced and described in a way to extensively highlight their discourse, being more so representative of ideology than people. Ideology explored at great length, that very directly interacts with the likes of Marius, and is a key proponent in the insurrection- yet again conveying the marriage of thought and action, sentiment and intellect.

So, there are two sides to Les Misérables – as has been deduced – the digressions, and the narrative (which includes the characters). Now I will make a grander, bolder statement: that of the underlying philosophy of political fiction as a whole – that philosophy being the one present in Les Misérables, and many other works from Dickens to Orwell. Another question: What is the purpose of political writing? To persuade – how does one persuade? Through thought and reason, appealing to intellect. This is predominantly how essays are often designed. However, there are two issues: 1) humans are for the most part not logical thus an argument formed exclusively this way is unlikely to be effective to a general audience, and 2) often pure reason inevitably fails as you tend towards more complex philosophical ideas which we are all disposed towards – politics and philosophy are not exact sciences. Hence the ‘fiction’ of ‘political fiction’. Humans are naturally empathetic creatures, and thus most are more willing to interact with that of the narrative story than that of the academic essay, as is with the overwhelming popularity of narrative-driven entertainment, or (a more relevant example) the usurping of the musical adaptation of Les Misérables over the original source material. Although the term ‘mindless entertainment’ is a rather distasteful phrase, it is a shame a vast majority of the population sees media this way. Thus I would argue that embracing the aspect of pathos in these works is useful – if not completely necessary to effectively convey ideas of a political nature. This pathos is very much emphasised in the work of Charles Dickens, for example in A Christmas Carol, where the reader is directed to pity the Cratchit Family (in particular Tiny Tim), and thus reflect on the poverty of their own world and themes of social responsibility, similar to those found in Hugo’s novel.

There is however a problem with the way audiences respond to such works, with many seeing attempts at a greater meaning to be incompatible with the story or plot, showing a direct refusal to engage with the author. Hence the rejection of Hugo’s digressions as unnecessary or detrimental to the work as a whole, and the ultimate devaluation of art in the eyes of the consumer. Understand this is not a case I make against ‘mindless entertainment’, as there is nothing inherently wrong with it – rather it is a case against ignorance: ignorance of art and ignorance of suffering. After all, art is inherently abstraction – it is the form that this abstraction takes that varies. This may appear counterintuitive to my case of realism in Les Misérables, but that is not so. The ways in which this novel highlights reality, being a conscious and creative choice, is thus a form of abstraction, the painting of a truth, with the art of painting being the deciding factor of said abstraction. Attention is brought to this fact and thus should be recognised. Perhaps a more obvious example to illustrate my point is Andy Warhol’s Empire– a seven-hour ‘film’ of nothing but the Empire State Building, with no shot changes or any narrative structure. It is very much realism in the most literal aspect, though as with most modern art, this seemingly simple decision is what is brought attention to, with Warhol himself commenting on how the purpose of the film was “to see time go by”, bringing attention to a creative choice that is very much part of the abstraction that is art. It is this layer of meta-commentary that can be derived from both Les Misérables and Empire, commentary on the nature of the novel and film as mediums and how they relate to the real world, that is part of the art, as I am of the philosophy that all creative decisions, intentional or unintentional, are part of the beauty of art itself. All tools used are tools that should be considered, including Hugo’s digressions and Hugo’s characters.

The great film critic Roger Ebert once likened films to “machines that generate empathy” a phrase that can be used to describe all mediums of artistic expression, not in the least Les Misérables with its sprawling struggles and romance. Whilst Hugo’s digressions make a case for the logos, that at times can be rather difficult and daunting (and very long), it is in fact one and the same with pathos: the mind and the heart are of the same body. Perhaps that is what all great political fiction accomplishes, or what it should aspire to achieve.

Comments ()