What is the Euro’s most fundamental problem?

Jack Downey

The Euro was established in 1999, with 11 countries adopting the single currency. Now, the Euro is the currency of 20 European Union states known as the Eurozone. Superficially, the increased membership of the Eurozone suggests that the single currency has been successful. However, the Eurozone continues to face the fundamental problem of internal economic heterogeneity that will require the development of new policy instruments to address. The Euro was created to cultivate greater economic and political union and prosperity by taking advantage of economies of scale, Ricardo’s comparative advantage, and facilitating trade between Eurozone countries. While the Euro aimed to create a closer economic and political union, the problems associated with the Euro’s implementation have resulted in economic divergence rather than convergence. This has been accompanied by the rise of Eurosceptic populism in many Eurozone countries. The introduction of the Euro, therefore, has ushered in the reverse of its intended consequences.

Economic Consequences of the Euro

The Euro’s introduction occurred despite several member countries not satisfying the requirements laid down by economic theories for adopting a successful monetary union, such as the economic convergence required by the Optimum Currency Area theory (Mundell, 1961).

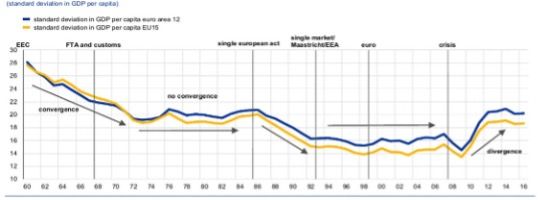

Figure 1 Economic Convergence in the Eurozone

Well before the Euro was introduced, leading economists, such as Krugman (1993), voiced their concerns. Krugman argued prophetically that monetary union would lead to increased specialisation, diverging economic structures, asymmetric development, and widening differences in growth rates. The early years of the Euro were relatively calm (see Figure 1) in comparison to what was to happen later but, in reality, the problems of the Euro were being hidden from view by increasing levels of private and public debt, particularly in the weaker Eurozone economies; storing up problems that would lead to the sovereign debt crises and the potential collapse of the Euro project and possibly the European Union itself.

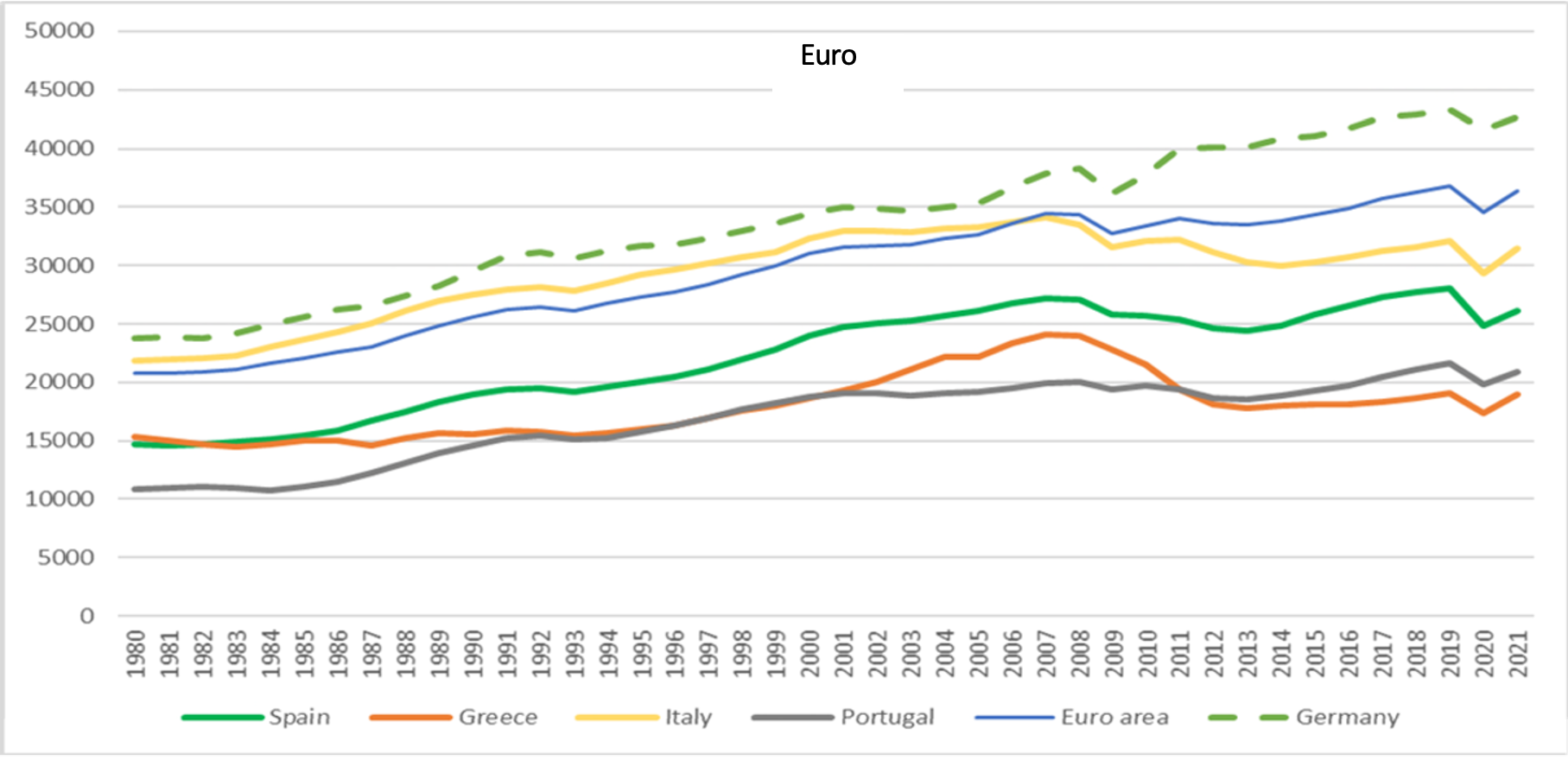

Figure 2. Real GDP per capita in some Euro area countries

In the Euro’s early years, weaker economies such as Italy, Portugal, and Greece displayed poor export performance, and imported more goods and services, particularly from stronger economies, such as Germany, which had higher productivity rates. Coupled with the fact that they were already producing exports at a higher rate relative to weaker countries in the Euro, the stronger economies enjoyed a considerable competitive advantage. Moreover, a fixed exchange rate decreases risks associated with trade, such as exchange rate fluctuations, and encourages greater trade. In the context of the Eurozone, the incentivisation of trade led German (and other strong exporters in the Eurozone) to export in even greater quantities. Compounded by the fact that their productivity rates (unit per output per unit input) were higher than other countries, their exports were more competitive (production costs were lower per unit produced). This, in turn, increased their growth rates (especially Germany), as they continued to run supernormal balance of trade surpluses on the current account of the balance of payments, leading to further economic divergence from the weaker Eurozone economies, as exemplified by the widening gap in the GDP growth rate in figure 2.

Before the introduction of the common currency, the weaker countries would have had a floating exchange rate mechanism, which would have corrected these trade imbalances by making exports of the weaker states relatively less expensive, and the exports of the stronger states more expensive.

However, with the single currency in place, there is no self-correcting mechanism that can address these imbalances in the Eurozone. Moreover, business cycles within the Eurozone can be different, so when asymmetric shocks occur, appropriate adjustment mechanisms are not available that correspond to the needs of all Eurozone economies (Marelli et al. 2019). The structural imbalances within the Eurozone were masked by greater levels of private and public debt with funds available from major European banks. This was, again, the consequence of the introduction of the Euro as European banks had greater confidence in lending money as their fear of weaker states devaluing their currencies and increasing inflation as a means of reducing the public debt burden had, in their minds, been eradicated.

The problems created by the lack of a floating exchange rate, however, do not end there. As stronger economies continue to export more and grow more, the Euro appreciates. The further appreciation of the Euro does the opposite of what a correcting mechanism would do for weaker European countries, further increasing imports and decreasing exports, exacerbating the problem. The weaker economies were, therefore, caught in the start of a ‘doom loop’ of falling competitiveness and higher debt. The European sovereign debt crisis was, therefore, not an externally generated event but inherent to the Eurozone’s design.

Policy Responses to the Sovereign Debt Crisis

What policies could the weaker countries adopt to address these issues? The traditional response to such a situation would be currency devaluation, but again this was not possible due to the Euro. A second possible policy for the southern European countries is a fiscal response, such as Keynesian anti-cyclical fiscal measures. However, such a phenomenon would be exceedingly difficult due to the fact that ‘Under the terms of the EU's Stability and Growth Pact, Member States pledged to keep their deficits and debt below certain limits: a Member State's government deficit may not exceed 3 % of its gross domestic product (GDP), while its debt may not exceed 60 % of GDP’. The European Central Bank controlled interest rates with a mandate to control the inflation rate and money supply. Hence, traditional monetary policies of national central banks were out of the question. This monetary and fiscal policy straight-jacket essentially rendered it impossible for the weaker countries to gain economic ground on the stronger European countries.

The European Central Bank (ECB) is also faced with a dilemma. With stronger countries of the Eurozone prospering at the expense of weaker economies and the weaker falling behind with their spiralling deficits, does the ECB adopt a monetary policy which is advantageous for the thriving countries or a policy for the struggling countries? The central problem is that ECB interest rate policy and quantitative easing apply to all of the Eurozone, irrespective of the economic conditions in individual states. It is very difficult to redress these imbalances as the Eurozone does not have the necessary fiscal policies in place, such as common public investment, to help lagging regions and countries to introduce structural reforms (Marelli et al., 2019). The structural funds available to the EU have been small, and hence, have had marginal effects. The EU only spends around 1% of its GDP- a figure in stark contrast to countries such as the USA, which spends around 20% of its GDP (Stiglitz, 2016). Therefore, one could argue that the limited budget has systematically undermined valuable long-term plans such as the EU 2020 strategy, such as the old Lisbon Agenda (Marelli et al., 2019). Given the impossibility of currency devaluation and the lack of a fiscal policy, the only alternative was austerity imposed on the weaker countries and internal devaluation through falling wages and prices. This caused high unemployment and many social problems, adding fuel to the burning fire of Eurosceptic populism seen in many EU nations. Many weaker European countries suffered the often-tragic consequences of internal devaluation. It is almost as if the ECB and the EU's inability to appropriately respond was another feature inherent to the Euro's design.

Rising Political Discontent in the European Union

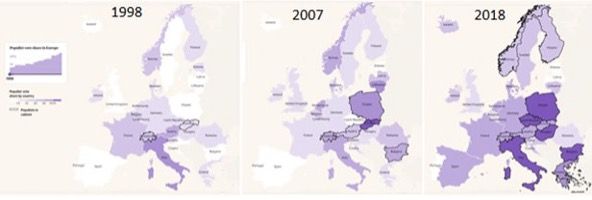

In such circumstances, it is hardly surprising that political discontent and unrest manifest themselves in stronger and weaker economies alike. The weak blame the strong for their economic imperialism, and the strong blame the weak for their lack of productivity. Although the rise of right-wing populism is both a cultural and economic phenomenon, the sovereign debt crisis and its aftermath have impacted the rise of right-wing ethno-nationalist parties across Europe, some of whom have gathered substantive support – allowing them to form governments (see Figure 3). The rise of such parties, especially in the Eurozone, has acted as a brake on European integration. Far from creating the conditions for an ever-closer Union, the Euro has ironically driven a wedge between European countries.

Figure 3 Populist vote share in Europe and the Eurozone

Conclusion

To what extent can European policies be re-designed to overcome this fundamental problem of economic heterogeneity and divergence? One of the few positive consequences of the covid global pandemic has been the creation of a Next Gen EU fund of 750 billion euros funded by European sovereign bonds to help those states most badly affected. It is a clear break from the austerity policy such as those adopted after the financial crisis of 2007–2008 and earlier. It also creates precedence in creating a common European debt and fiscal policy that could, in principle, be adopted to address future economic crises instead of the pain of internal devaluation. Whether this belated display of European solidarity from the stronger states in the creation of common bonds will be enough to reconnect the bonds of the EU states, time will only tell. However, it appears that there finally is recognition of the need for a common monetary policy but also a fiscal policy that can aim to correct structural imbalances between member states.

References

Diaz del Hoyo J. L., Dorrucci E, Heinz F. F., Muzikarov S. (2017) Occasional Paper Series Real convergence in the euro area: a long-term perspective, European Central Bank, Working Paper Series n 203, pp1-120

Krugman, P. (1993), “Lessons of Massachusetts for EMU”, in Torre, S. and Giavazzi, F. (Eds), Adjustment and growth in the European Monetary Union, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 241-261.

Lewis P, Clarke S, Barr C, Holder J and Kommenda N. (2018), Guardian, 20 Nov 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2018/nov/20/revealed-one-in-four-europeans- vote-populist

Marelli E. P., M. P. Parisi and M. Signorelli (2019) Economic convergence in the EU and Eurozone, Journal of Economic Studies, Vol. 46 No. 7, pp. 1332-1344, DOI 10.1108/JES-03-2019-0139.

Mundell (1961), A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas, The American Economic Review, Vol. 51, n. 4, pp. 657-665.

Stiglitz J (2016), The Euro: How a Common Currency Threatens the Future of Europe, W.W. Norton, UK pp. 1-416ISBN 978-0-393-25402-0)

Comments ()